Blockers versus enablers

As many of you will know, something I’m very interested in is the value of public servants’ time. When I first launched the Meeting Cost Calculator, a lot of the early feedback I got was how useful the calculator would be for other, non-meeting public service activities as well. You could use the calculator to estimate the total cost of writing and reviewing a briefing note, to fill out the paperwork for a leave request, to complete the travel claim process, etc.

Part of what motivated creating the calculator is the belief that public servants’ time is valuable – something that isn’t always appreciated by senior public service management, the public, and public servants themselves. The public service is often seen as cautious, risk-averse, and perfectionist. The hierarchy of public service institutions compound this, as documents and other products get carefully reviewed and wordsmithed at each layer. All told, these tendencies create an environment where getting things out the door is a challenge.

The organizational dynamics in these situations are sometimes hard to talk about; one person’s due diligence reviews are another person’s unreasonable delays. In today’s context, however, where the public service is being asked to respond more quickly to evolving social needs, being able to get things out the door quickly (and continue iterating once they do) is more important than ever.

As a model to describe behaviours that either support or prevent things from getting out the door, “enablers” and “blockers” is a convenient (if simplistic) shorthand. Enabling versus blocking is a property of the behaviour of people in management or gatekeeping roles, and of the institutional structures that incentivize certain behaviours. It’s worth remembering: people aren’t blockers, although particular actions they take might sometimes be. And, blocking behaviours almost always have good intentions at their root, even if the consequences ultimately outweigh the benefits.

Blockers as a function of time

As a public servant trying to get something approved up the hierarchy, the simplest definition of blockers versus enablers might be a “no” or “yes” at each level. Changes and edits from various layers of management can feel like a blocker each time (even if these changes are ultimately improving the document or product).

“Yes” and “no” isn’t the whole story, however; the time it takes to receive these is a bigger factor. (In practice, more frequently, it’s the time it takes to receive some kind of edit or revision to the document). A “fast no” with a series of changes that will then let the document keep on moving up is more valuable than a “slow yes”, where the document is approved as-is but only after weeks or months of sitting on someone’s desk.

In environments where shipping things quickly matters (which, ideally, would include most of the public service), “slow yesses” and “slow nos” are practically equivalent. In some cases, the “slow no” or “slow yes” are deliberate institutional strategies – to take so long to review or approve something that the originating party ultimately gives up.

Overcoming blockers as a function of time often depends on setting clear expectations for timelines and getting pre-approval for things long before you need it. Here are some potential strategies:

- Providing clear deadlines when you’re asking for feedback, and being clear about what things you want feedback on

- Whenever possible, explicitly frame requests as “for input” instead of “for approval”, so you can keep moving if recipients don’t respond

- When you need approval from groups outside your own hierarchy, do this in parallel, not in series (e.g. ask each group, separately, all at once instead of one after the other)

- Get formal pre-approval in writing for activities you might need to do down the road, far ahead of time

Blockers as a function of quantity

Public service institutions often have a large number of actors that need to review or approve things intended for public consumption – content reviews, privacy reviews, security approvals, project governance, etc.

Even if (in best case scenarios) these various committees and gatekeepers are supportive of a project’s goals, getting all of them to individually green-light a document or product can be very difficult. One group’s proposed changes can cause another group to have second thoughts, and maintaining the simultaneous approval of everyone involved for long enough to actually get something out the door can sometimes seem impossible. Shepherding this process falls to the original team, and each actor involved may not realize the combined burden that they and every other actor cumulatively imposes.

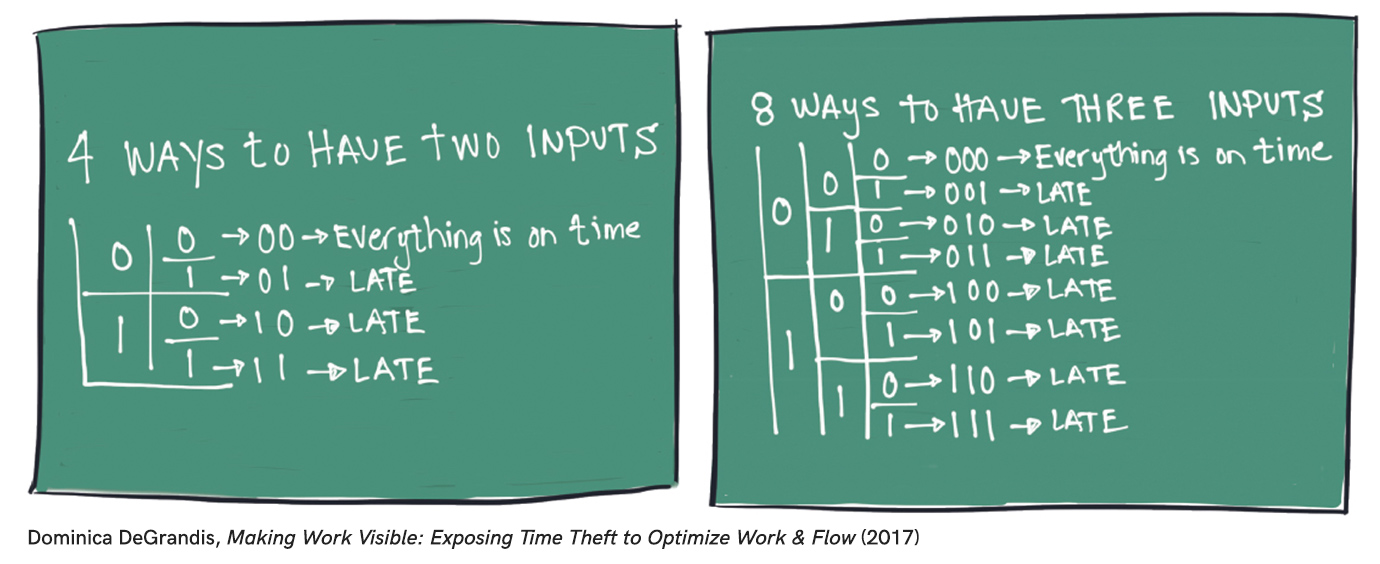

In many cases, the quantity of approvals or reviews required acts as a structural blocker, regardless of how positive or supportive individual reviews are. Dominica DeGrandis’ Making Work Visible book provides a useful mathematical model for this:

If there are two inputs needed to deliver something, then there is only one chance in four of delivering on time. One chance in 2^n is the formula that computes the total number of binary permutations.

If each given actor needs to green-light a product (providing either a “yes” or “no”), then every additional actor doubles the number of possible states.

There’s only one state in which the product is fully green-lit (when everyone says “yes”). With two reviewing actors, there’s a 1 in 4 chance of being green-lit. With three, there’s a 1 in 8 chance. With four, there’s a 1 in 16 chance, and so on.

In typical government departments, 16 different groups might need to approve a given project – that’s 65,536 possible states (2^16), and only one state where everyone agrees. It’s not great odds.

Overcoming blockers as a function of quantity ultimately comes down to, reducing the number of external approvals or reviews that are required. Some strategies for this include:

- If you can, influence the design of internal processes to have as few external dependencies as possible

- Delegate formal approvals as far down the hierarchy as possible, and trust your staff to make decisions autonomously

- Decouple “go-live” decisions from committee or governance reviews (in favour of continuous, incremental improvements), and get permission to do this from the very beginning

What does enabling look like?

Although this post doesn’t paint an optimistic picture, good work gets done in the public service all the time. In a lot of cases, that’s thanks to thoughtful public servants in management and leadership roles, who champion their teams’ work and fend off potential blockers when needed.

The public service leaders that I look up to most embody a combination of humility and trust – hands-off and confident in their teams to make good choices and do good work, but ready at a moment’s notice to step in and shield those teams from external delays, gatekeepers, and threats.

It’s striking how rare, and how powerful, a statement like “endorsed, with no changes” is in a rigidly hierarchical environment like the public service. It’s an expression of trust – both in a team’s capacity to implement, and in the value and urgency of their work.

The metaphor for enabling public service leadership that comes to mind (you’re welcome, Star Trek fans) is of a starship in orbit. You trust the away team to do what works best on the ground, but you’re on standby and ready to act when needed. Just knowing that you’re there, and that you have the team’s back, sometimes makes all the difference.

For more on emerging styles of public service leadership, this recent piece from Abe Greenspoon and Jennifer MacLeod is a great read.