Make things open source, it makes things better

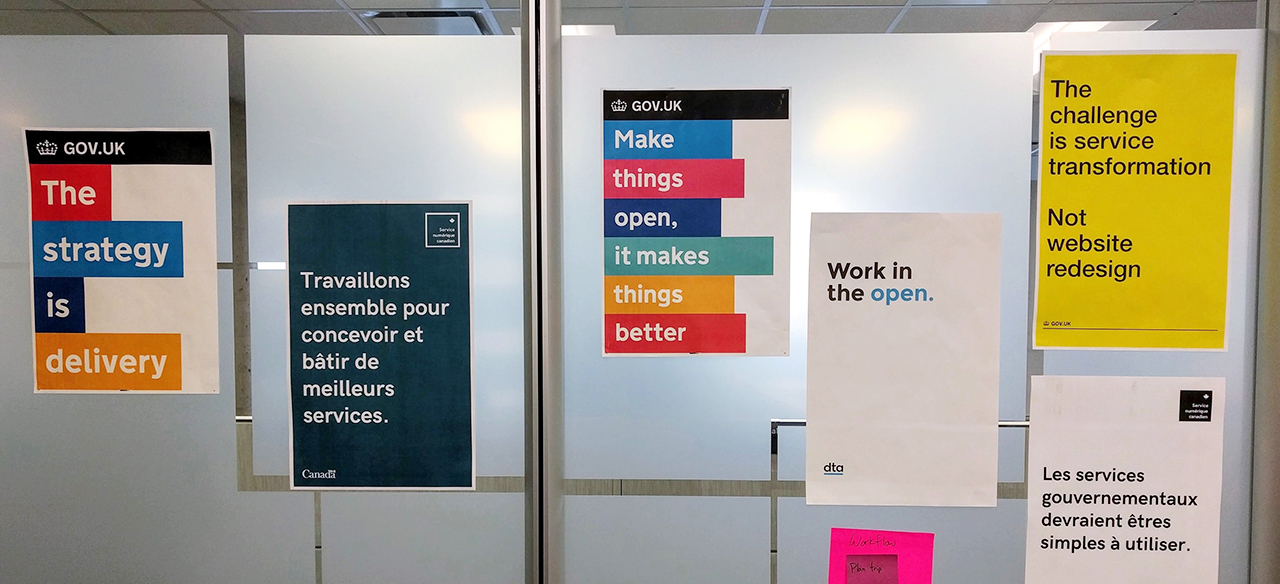

One of GDS’s early design principles was “Make things open: it makes things better.” I printed off a poster of it that I would stick on the wall near my desk, back when our then-tiny team moved desks every couple months.

Making things open follows a long tradition of open government advocacy, open science movements, and public sector transparency initiatives around the world (Prof. Tracey Lauriault has given fascinating presentations on this). But in the government technology field, GDS changed the game by making things open a foundational starting point for how they worked. From GDS’s blog and social media updates to the software they published in the open on GitHub, they set the bar that every digital services team following in their footsteps has tried to live up to.

The “open source” part of open

When it comes to software being developed by or for government institutions, making things open source is such an obvious choice that it’s hard to believe, until recently, that it was treated with a lot of doubt and suspicion: “Could anyone just edit your code?” “What if people find security flaws?” “Who needs to approve publishing this?” Governments’ reluctance to either use open source software, or publish software they created or paid to create, became an increasingly stark contrast with the enthusiastic adoption of open source by almost every major technology company.

Even today, open source software is seen as a bit of a niche in the federal government IT landscape. Back in February, my colleague Josh and I published a blog post that attempted to dispel some open source in government myths:

Building software in the open brings out the best in people’s work. It helps us learn from each other, and makes it easy for people to continue contributing to useful software even as they move from one part of government to another. Open source saves time and money, by making software easier to reuse and adapt.

Making open source the norm for government teams building or procuring software is something I’d really like to see happen. Teams across the federal government are advocating for this, to increase the speed, quality, and interoperability of government software. Other countries (like France and the UK) have blanket policies requiring that custom software code paid for by government is published as open source. It’s something Canada should do too.

When public trust matters most

A few weeks ago, our team launched COVID Alert, a Canada-wide exposure notification app. Public trust in the app – that it respects people’s privacy, works reliably, and doesn’t do things they don’t expect – was (and is) a critical factor to the app succeeding or not.

Making the app clear and easy to understand (through content design and continuous design research) was an essential ingredient for this. Making it open source was the other essential ingredient (not least because the app was based on COVID Shield, an already open-source project!) Being able to see the software code inside and out, at least for security and privacy experts, was “table stakes” for public trust. Asking people to trust an app whose code wasn’t open source, for a subject as sensitive as being exposed to COVID or not, seems like a complete non-starter. Other countries with similar exposure notification apps – Ireland, Italy, and Germany – have all made their apps open source as well.

The apps and services that underpin government programs should practically always be open source. Public trust in things like the EI system, filing taxes, or as a public servant, getting paid, would be higher if people could see the inner workings and understand that software is working as it should.

Old and outdated software is the one area where making things open source can be a challenge. Going through thousands of lines of legacy code, looking for glitches or security issues, isn’t an easy feat. But for new code – even code that talks to legacy systems that aren’t open source – making it open source should be the default, in practically every public service team. Whether it’s built in-house or by an external vendor, if you want people to trust your code, make it open source.

Don’t pay twice

Waldo Jaquith, a government technologist in the United States, has a fantastic recent post on why government software should be open source:

When it comes to important state infrastructure, top government software vendors use a double-dip business model. First, they charge us to build the software, then they charge us to use it. Nobody would pay to build a house and then pay to rent that house, so we shouldn’t do this with important state infrastructure. Vendors often claim that states are merely licensing software they’ve already built (“Commercial Off-The-Shelf,” aka “COTS”). This is often untrue. Instead, the software they’ve already built is custom for another state and will require large changes to work in a new state. These changes will be done at our collective expense, but with the resulting software owned by the vendor. In this scenario, we’re paying for a house to be rehabbed before we start to pay rent on it. This is absurd.

Open source code reduces vendor lock-in, improves the quality and interoperability of software, and increases public trust. What’s not to love?

Hat-tip to Lena Trudeau, both for introducing me to “table stakes” as a catchy expression and for fearlessly advocating for open source in government!