Tools that work

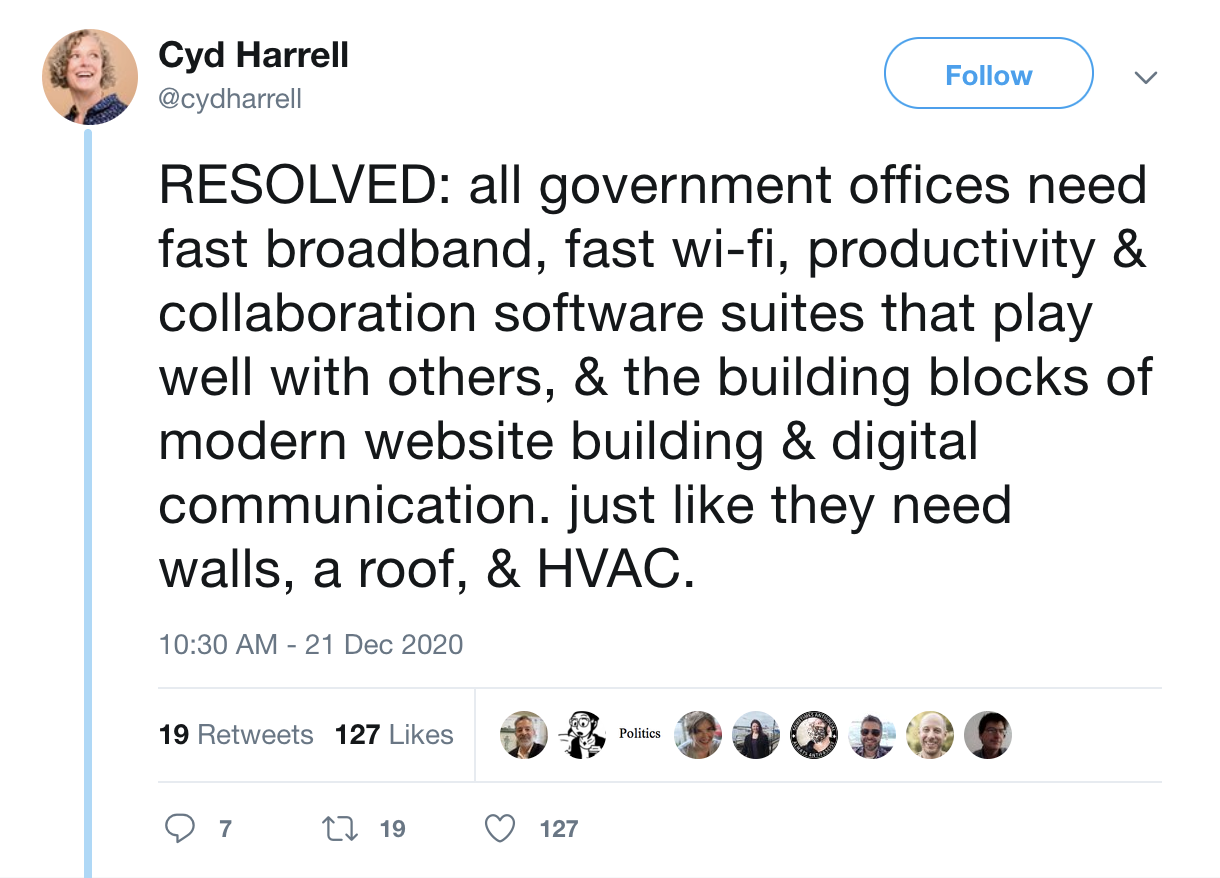

Cyd Harrell posted a great Twitter thread last week, that friends of mine will know is definitely my kind of content:

The article that accompanies that thread – Is innovation really making cities better? – points out that city governments across the US lack even 1990s-era technology. The same is true of governments at every level here in Canada, too. Public servants do critical, life-changing work with the most rudimentary tools.

I don’t think it has to be this way, and my experience in government so far makes me dream of all the good work that could be accomplished if public servants had access to better tools. Making that happen is a big part of my own public service mission.

A blast from the past

My first experience in the federal government was in grad school, as a student working for the team at Global Affairs Canada that rebuilt Travel.gc.ca in 2012. It was a whirlwind, eye-opening experience, with an amazing and inspiring team of colleagues and a project with a frantic timeline. I pulled a few all-nighters at the Pearson Building, we may have broken a few rules, and we launched a website that won government-wide awards. All of those are stories for another day.

What stood out, unsurprisingly in hindsight, was that my work computer was only equipped with a word processor, an email program, and a web browser (Internet Explorer, of course). The word processor was WordPerfect 7, the same version that my family used when I was in elementary school in the late 90s and early 2000s.

This tweet from Rachelle Gervais (a friend at Global Affairs) captures the kind of reaction I had, too:

Welcomed a coop student last week. She is helping us with social media and some graphic design. Felt very embarrassed when IT installed Photoshop 2005 on her PC. She was 6 years old when that version came out. Come on #GC, we need better tools. #GCDigital

— Rachelle Gervais (@Rachelle2pt0) January 17, 2019

I rejoined the federal government in 2016, after spending several years working as a software developer for a tech startup. Once again, the work computer I was assigned (a Surface Pro tablet with a docking station) was a disappointment; the office suite was newer but the choice of software was essentially just as limited as my old Global Affairs desktop. Internet Explorer was, of course, still the only browser option.

My personal MacBook wasn’t anything fancy; a bit beat-up from working and travelling overseas, but it was kitted out to do all kinds of work. Building small websites, designing posters for volunteer groups, doing very rudimentary data science work – it was a well-equipped toolbox. In comparison, the work computer had practically nothing. Using it was like opening a big toolbox and finding it only had a toothpick inside. No one can be expected to do great work on bad equipment.

Better environments for better work

Fortunately, I joined a team that was enthusiastic about shaking things up. Part of my early work was figuring out ways to equip my colleagues with modern equipment – as my UK heroes would say, technology “at least as good as people have at home”. That included MacBooks as our official (unclassified) workplace devices, unfiltered wi-fi, and the ability for team members to install the design and software development software they needed onto their devices by themselves.

As I wrote in a 2018 work blog post,

Developers and designers have a lot of job options, and making the Government of Canada an attractive place to work for digital professionals is a key part of CDS’s mandate. As government departments looking to build better digital services, we all need to be able to offer modern tools in order to successfully recruit talented staff.

None of this was really revolutionary – the UK had been doing all the same things 3 or 4 years earlier – but it was striking how unusual it seemed in the Canadian government. Part of this, looking back, really illustrates Leah Lockhart’s theory that poor-quality government IT trains public servants to have low expectations of what’s possible.

Even the simplest things (by any outside-of-government metric) could seem impossibly futuristic. On one memorable occasion in 2017 or so, I showed a senior public service executive how to use Google Docs for the first time. They were amazed, watching changes to a document on one computer show up in real-time on another computer. (Google Docs publicly launched in 2006; as I joked later, most executives’ kids probably use it on a regular basis in elementary school.)

Being in an environment where I could help introduce colleagues to better, more productive and user-friendly technology has been really fulfilling. Friends in other parts of the public service have gotten in touch on a regular basis over the past few years, asking for suggestions on how to get better technology into the hands of their own teams and departments. Others have gotten in touch, discouraged, as they ponder leaving the public service because they don’t have the tools they need to do the specialized work they’re experts in. Denied IT request tickets have a much heavier cost than people tend to realize.

Making these changes is hard, given the centralized decision-making for software and devices in most departments’ IT divisions. They’re important changes, not just to be able to recruit design and tech folks into government from outside, but also to make it possible for existing public servants to skill up. Educational programs (like the Canada School of Public Service’s excellent Busrides series) aren’t enough if people don’t have an environment where they can experiment with and learn technology-enabled skills during their day-to-day work, even (and especially!) if they work outside of IT-related divisions.

All of these conversations were the inspiration behind “Is this blocked in my department?”, which helps illustrate which websites and tools are either available or blocked in each federal department. Its pandemic-inspired sibling website, “Should it be blocked in my department?” aims to better equip public servants to have those conversations with their IT groups and CIOs.

The trends are alright

Things are getting better; in many ways the COVID-19 pandemic jump-started a lot of work to bring public servants into the modern era as all of us were suddenly forced to work and collaborate from home.

Even before the pandemic, some really good work had been happening to open the door to more modern tools for public servants. TBS’s 2018 IT Policy Implementation Notice instructing departmental CIOs that they shouldn’t block access to online services and collaboration tools was a major turning point (thanks to really excellent work from Alex, Imraan, Po, Scott, and many others).

Unblocking websites is really just the beginning, though. Being able to easily pay for team subscriptions to online tools, being able to install open source data science tools locally, and being able to use modern tools with protected information are all as-of-yet unsolved issues.

The bigger issue, on top of this, is the wildly uneven distribution of access to tools between departments. Comparing the highest- to lowest-scoring departments on Is this blocked? is illuminating. Competition for talent with design, technology, and data science skills is only going to get more intense in the post-pandemic period, not just between the private and public sector but between departments as working from home and distributed across the country becomes a more normalized option.

On top of a sense of mission, good team culture, and relevant work, access to an effective working environment is a clear reason to choose one department over another. The departments with the best tools are going to get all the best people. Are departmental CIOs and heads of HR talking about this?

A lot of conversations about technology in government involve flashy, sales-pitch-driven futuristic ideas. In my mind, those aren’t convincing, and they’re not even that interesting. To me, the most interesting work in the next few years will be getting everyday technology – used in every other industry – into the hands of public servants, and seeing what they can accomplish with it.

As Cyd Harrell writes,

Every city has pockets of problem solvers who quietly invent smart improvements using the tools they have, without the shine that a formal innovation group or outside consultant provides. It is the people programming workarounds in Excel spreadsheets or running lunchtime learning groups on mobile web design that are pushing cities forward. They may think of themselves as problem solvers rather than innovators, but the root of most useful inventions is properly defining the problem to be solved. When these government staffers are given resources and attention, they can move mountains.

All of that is true for provincial and national governments, too. Let’s make it happen.

Cyd Harrell’s book – A Civic Technologist’s Practice Guide – is a gem. Definitely worth a read!