Crisis, bureaucracies, and change

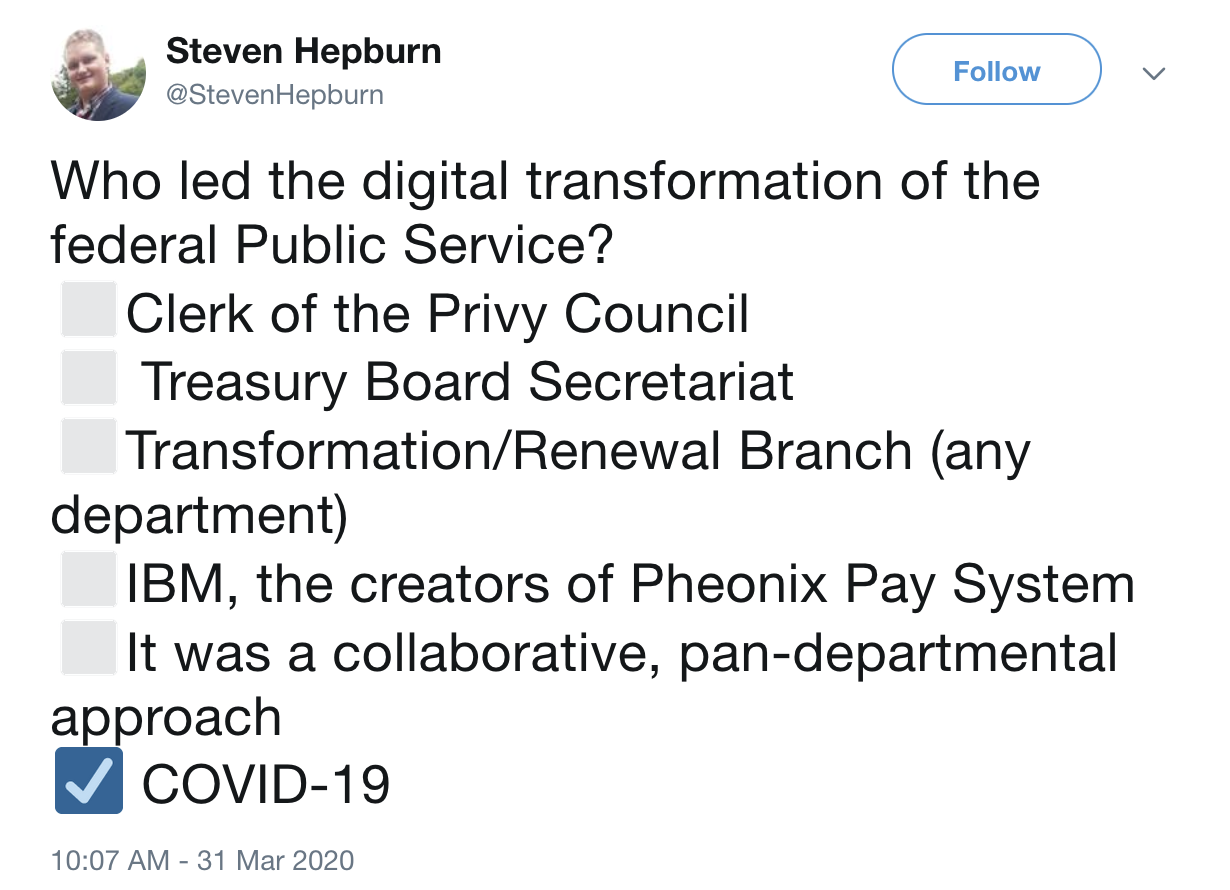

It’s been two months and a bit since the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically adjusted life in Canada. Amid the social and economic upheaval that took place, government responses – public health activities, emergency benefit programs, and more – have played an essential role. Government departments have rolled out benefit programs to Canadians in record time, with politicians and public servants alike developing and iterating on programs at an unprecedented pace.

As an enthusiast for public sector reform, it’s been genuinely encouraging to see the public service in Canada rise to the occasion. It’s a noteworthy moment, and some recent publications have captured what’s different between the present and “business as usual” in the public service. An April piece from Matthew Mendelsohn says it well:

…we can internalize the lesson that making adjustments to programs in real-time based on new information should be easier; that front-line staff and stakeholders will understand how programs are being experienced on the ground; and that acknowledging that something can be improved once it has been launched should not be interpreted as a catastrophic failure. At the end of the day, every program should be designed to achieve a clearly defined outcome. If evidence accumulates that programs are coming up short, processes must be designed to allow for recalibration.

The most striking difference between the public service in crisis-response mode and the status quo is its willingness to accept risk. In the same piece, Mendelsohn writes:

Normally, dozens of public servants poke and prod at every line and every number in a policy proposal, asking questions that are impossible to answer, with the goal of eliminating any risk that the program will be inefficient. What usually emerges is a watered-down program, with easy to achieve but meaningless metrics and accountability driven by conformity to process. Under ordinary circumstances, processes are designed to eliminate perceived risk of any new initiative to near-zero.

What we are seeing is the exact opposite. Governments know there are huge risks inherent to the programs that are being offered, but are willing to take them. In ordinary times, any one of the risks that are currently accepted would be enough to kill a new program. That’s why it is generally so difficult to get innovative, risky new programs launched.

Again, governments can’t just switch from risk-aversion to risk-seeking. But there are lessons to internalize: the risk of doing nothing is often greater than the risk of change, yet government systems are designed to kick the stuffing out of any new proposal, without probing deeply the risks of the status quo.

In a Twitter thread on the CERB application process, Aaron Snow describes the pivot “from ex-ante to ex-post eligibility enforcement” that made the application experience so seamless. Under normal circumstances, government benefit programs are usually designed with complex upfront approval criteria (designed to reduce the risk of fraudulent payouts) – but these add delays, errors, and time-consuming follow-up stages to the application process.

In many cases, people either don’t bother applying, or aren’t successfully able to, and miss out on benefits they would actually be eligible for. The CERB model (immediate upfront approval, and down-the-road eligibility reviews) addresses that in a clear way, thanks to some clever programming and a more thoughtful approach to risk.

Will it stick?

Despite some hiccups (network capacity, for example), the federal public service has adopted a number of changes to work more effectively during the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes guidance from the Treasury Board Secretariat that encourages the use of online collaboration tools like Slack and Google Drive in order to reduce the strain on departmental IT systems.

In the immediate reaction to the crisis, many government departments streamlined internal processes or temporarily exempted teams from needing to follow them. In institutional settings with an overabundance of process, this is a welcome thing. Trusting public servants to use their best judgment and to focus on outcomes over processes – and having power delegated to working-level staff to do so – should be the everyday norm.

A friend in another department reported that, after 5 or 6 weeks, their department re-imposed the cumbersome internal processes and external approvals that had been removed at the outset of the pandemic. Crisis mode – high trust and autonomy – reverted to business as usual.

Outside of crisis situations, it’s easy to get disconnected (as a public servant) from the actual impact of your work on people. If you get far enough away, your assessment of your own success becomes, “how well did I follow the process” rather than, “what impact did I have on Canadians” (or whichever population you serve). The urgency and constraints of working in a crisis force us to reconsider assumptions and processes that are long-established, and they also remind us of why our work matters.

In an April opinion piece, Tony Dean says it well:

…when this crisis subsides, Canada’s public servants should not go all the way back to normal. They should be empowered to continue embracing uncertainty, learning through experimentation, and continuing to work more collaboratively across sectors and jurisdictions to bring different perspectives to the table. Public servants want permission to innovate as much as Canadians would benefit from it.

Interested in ways to make crisis-mode changes stick? Nick Scott’s blog post on parallel learning structures is a great deep-dive into path dependency and strategies for change in government.

Kathryn May’s How COVID-19 could reshape Canada’s federal public service, published May 23, is also a must-read.