If you use project gating, you’re not agile

It’s probably not your fault, though.

There’s been a lot of interest in adopting agile practices in the Canadian government over the past few years. Being more incremental, iterating more quickly, and breaking projects into smaller pieces are all really valuable approaches.

One of the major challenges facing digital teams in government is that – even if they organize their own work according to agile principles – they’re operating within a broader environment with a lot of constraints all built on waterfall thinking. “Waterfall” project management operates on the assumption that each step in building a thing or implementing a project can be done linearly, with all the planning done at the beginning and all the implementing done at the end.

Construction and engineering projects (building a bridge, for example) are the classic examples of waterfall project management. You know exactly what river you’re trying to cross, how much traffic the bridge will have to handle, and based on that you can plan out exactly what materials, people, and equipment you need, and build it according to those pre-planned specifications. (Don’t do this.)

Software development – including any government IT projects – doesn’t work like this (much as waterfall project managers would like to think that it does). Any software that actually works needs to account for the unpredictability of human behaviour. Doing that well involves repeatedly getting feedback from the actual people that will use your software, and using that to continually improve what you’re building. Short feedback loops are the secret to good software (and good IT projects), and years-long, pre-planned waterfall approaches are a fundamental barrier to achieving them.

Documentation off-ramps, not implementation off-ramps

In the Canadian government, the main pressure to follow waterfall project management styles (largely abandoned by software companies outside government) originates from financial management policies, rather than information technology policies.

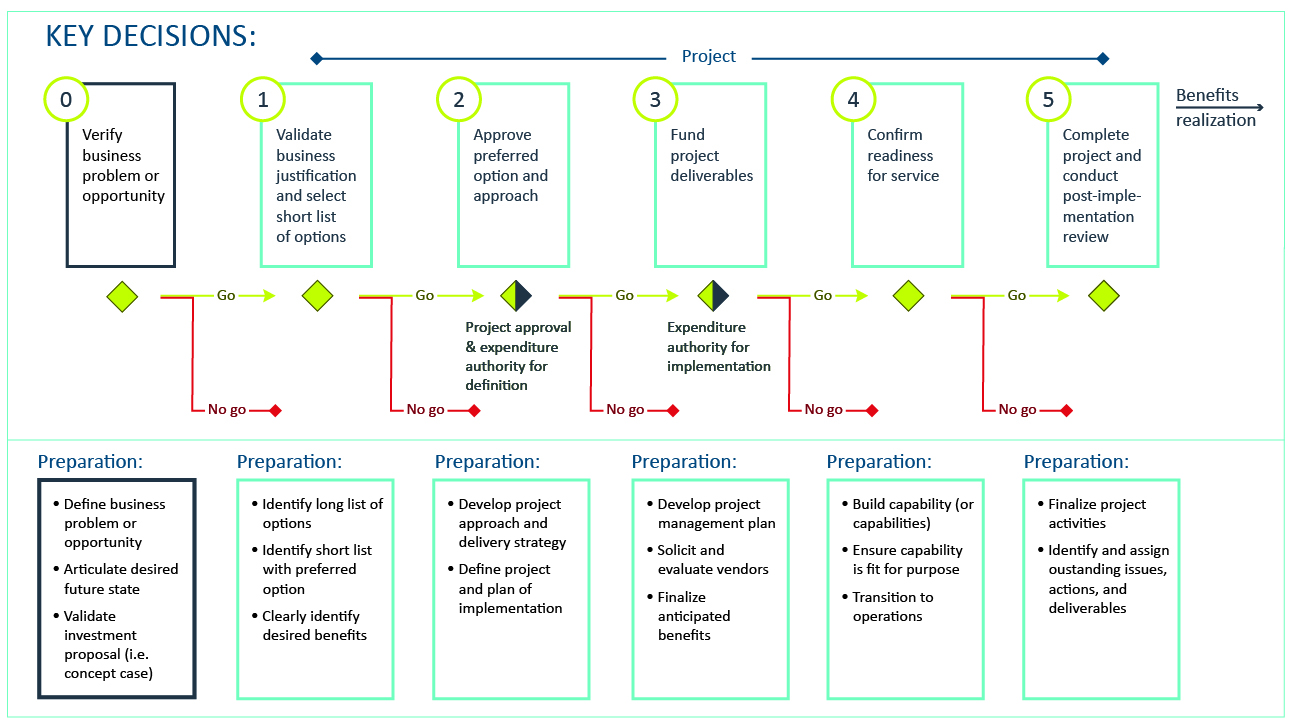

“Project gating” is the main form this takes, where – in a series of detailed planning steps – departmental teams seek approval (one gate at a time) to initiate a project, to get funding, to outline a project plan, an implementation plan, and a variety of other steps that eventually lead to building or procuring an IT system. Project gating requirements might be enforced by a department’s CFO office, their CIO office, a major projects management office, or some combination of all three.

The goals of project gating are ultimately to provide off-ramps where, for example, a poorly-defined or unnecessary project could be halted before it wastes more money. This is a worthwhile goal, and comparable in some ways to what I wrote about a couple weeks ago – splitting large projects into smaller ones that leaders feel more accountable for.

The critical difference, however, is that all of the project gating off-ramps take place in the planning stage, not the implementation stage. The careful, excruciating scrutiny that takes place at each gate – accompanied by hundreds of pages of documentation – all happen before any software is shipped, before any actual user sees it, and before any feedback or user research can come back in and improve what’s being built.

Teams going through the project gating process are challenged on the quality and comprehensiveness of their upfront planning documentation, which (in general) is not only a waste of teams’ time, it has a downstream effect of extensively solidifying or “baking” decisions into that documentation in a way that prevents the future iteration and responsiveness to feedback that’s required to build good software.

Project gating is designed to prevent expensive IT project failures, but it’s worth keeping in mind that all of the Canadian government’s most notable IT failures in the past decade successfully completed a project gating process. You may have heard of some of them.

The long way back

I was curious about the origins of project gating in the Canadian government, beyond the documentation that’s currently published on Canada.ca (last updated in 2021). The Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine is a fantastic resource for this.

The earliest reference I’ve seen to project gating is a 1997 TBS proposal for an “Enhanced Framework for the Management of Information Technology Projects”. It’s …not bad!

Gating also allows the department to control the cost of projects and minimize the financial loss on problem projects. In this approach, a designated senior departmental official, e.g., the project sponsor, manages the funds allocated to the project and releases only the funds needed to reach the next gate to the project leader. The performance of the project is reviewed at each gate, or when the released funds run out (to avoid delays, the designated official could release sufficient funds to permit work to continue on the project for a short time while this review and decision took place). After the review, departmental management can decide to proceed with the project as planned, modify the project and/or its funding, or even terminate the project limiting the loss to the amount previously allocated.

Projects and contracts will have to be structured to avoid incurring major penalties from the application of gating. By requiring the contractor to provide complete information on project performance and progress and also specifying in the contract when the scheduled reviews are to take place, the reviews could be conducted in a reasonable time without the need to stop work. By specifying the option to cancel the contract at the scheduled gates including the criteria on which such a decision would be made, in the contract, gating can be implemented without incurring major penalties.

Even from the outset – 25 years ago! – it’s noteworthy that TBS acknowledged the potential burden that project gating could incur. As written, this feels even more closely-aligned with the goal of breaking large projects into smaller components. (It presupposes, however, that work won’t be done in-house, which is both disappointing and prescient.)

Over the decades since, this idea transmuted into a more formalized set of gates, with increasingly-burdensome documentation requirements at each gate. This 2010 TBS document provides a detailed overview of what had by then become the “seven-gate model”. Departments, in turn, developed their own variations and frameworks based on the TBS guidance at the time, in some cases requiring teams to complete several competing project management frameworks simultaneously for the same project.

There is no waterfall-agile combo; it’s just waterfall

A lot has been written on the downsides of combining waterfall and agile approaches. Nevertheless this is probably the most common project management style seen in government today, as teams (like Honey’s) try to be as agile as they can within a broader financial and project management policy landscape that requires waterfall steps and documentation.

Here’s how Mike Bracken, the original director of the UK’s Government Digital Service, describes it:

Being agile doesn’t mean you give up on governance or deadlines. The idea that agile somehow “needs” a waterfall-type methodology to give it control and governance is nonsense. When you work in an agile way, governance is built into every step of what you do. You build and iterate based on ongoing user research. You build what users need, not what you guessed might be a good idea before you even started building. That means spending money throughout the lifecycle of a service. Not throwing a lot of money at a project upfront, without knowing if it’s going to be useful. Or not.

In my view, formalising a mishmash approach is going to end up giving you the worst of both worlds. You won’t get the thing you planned on the date you planned it, and you won’t get something that meets user needs either. You’ll end up with something that fails on both counts.

Paul Craig has an excellent post that speaks directly to the tension between shipping quickly – a key agile practice – and concerns around governance and oversight:

Is ‘Wagile’ a good idea? No. But how about starting fights with a bunch of people you work with and eventually having your project cancelled? Well, obviously that’s worse.

It’s not easy to subtract governance processes in an organization hyper-sensitive to risk (“let’s not do this documentation and still be allowed to release”). Removing something that looks safe (even a diagram that will soon be out of date) without an equivalent replacement is a tough sell.

Shipping early is the best argument you can make against the reality of waterfall, because, done right, you will save huge amounts of time and money. By the same token, the longer it takes you to get products built and released, the more you resemble the expensive waterfall processes you seek to replace.

This is why you need to move fast. In general, you want to define your MVP and then test it with users as soon as possible. Enterprise planning does not have a good answer to ‘user needs’, so it is important to prioritize early user engagement. User feedback both (a) gives you insight to improve your product and (b) functions as documentation you can share internally that other teams don’t typically have. Once you are confident that your product works, focus on what you need to do to get it released. It’s far better to have a released ‘alpha’ service than a highly-polished internal prototype.

Ashley Evans, Sarah Ingle and Jane Lu wrote a really fantastic post on a similar theme, on what it looks like to shift from planning to learning. They write:

The root problem is a desire to avoid failure by overplanning and creating a sense of false certainty.

From a structural perspective, this barrier shows up as excessive forms to fill out, briefings to give, or checklists to complete.

From a cultural or behavioural perspective, it shows up as top-down decision-making, discouragement of change, or critique without support to find an alternative.

We need to redesign go-live protocols and digital governance processes so that they are contextual, and encourage creativity, responsible design, and learning over compliance, oversight, and risk-avoidance.

Canada isn’t alone in having departmental funding models that reinforce outdated ways of working; written from the UK, Emma Stace’s excellent list of top issues facing government in implementing digital, data, and technology strategies captures this well:

Funding can be a root cause of poor technology. Technology funded as a capital investment or project with a start and finish date not only locks in legacy thinking about tech as a ‘cost centre’, it also increases cost, duplication and fragmentation by effectively starting from ‘0’ every time.

Change the way your organisation funds technology by determining its value, not its cost.

Waterfall opt-out strategies

For teams in government that want to be agile – hopefully that includes you! – one way to navigate these constraints is to not structure your work as projects, since formal project gating requirements originate in government-wide project management policies. Remy Bernard from ESDC’s IT Strategy team has a really interesting post that looks at this in more detail.

Projects by definition have a defined start and end date; most government services don’t “stop” at a specific point in the future. Structuring improvements to existing services (or the development of a new service) into a time-bound “project” is another waterfall side-effect that leads to semi-abandoned, legacy systems that still power critical public services but that don’t have an ongoing team or funding available to keep improving them. Projects are “done”, but software that’s actively being used by human beings never is.

In departments that have funding already available, teams might be able to describe their work – accurately – as an “initiative” or as a service, which is a better articulation of responsible stewardship of critical systems than a time-limited project would be. Some departments’ financial approval processes consider any initiative larger than $2 or $3 million a project “automatically”, making this strategy less feasible. If nothing else, that’s extra motivation to keep your IT initiatives small and incremental.

For departments that are seeking new funding, the strategy I’d strongly recommend is to seek funding for teams, not projects. This avoids baking untested assumptions into project plans and funding proposals. The team, once it forms, is better equipped to iterate, gather feedback, and change approach based on what they learn. And, ideally, they can continue incrementally improving their IT systems and services well into the future, beyond the constraints of a project end date.

One of the critiques of agile software development that frequently comes up is that “it’s workable for smaller, experimental projects, but it doesn’t work well for really big projects”. The truth (as one of Paul’s colleagues at GDS once said) is that no one has a process that works well for larger projects. Larger projects just tend to go wrong, whether you use agile or SAFe or PRINCE2 or any other project management approach. You just shouldn’t do mega-projects.

I’d love to see the project gating framework and related policy requirements be formally deprecated in the future; it’s a decades-old relic that has more downsides than benefits. Getting rid of project gating is asking a lot of senior public service leaders – to do things smaller and more incrementally, to trust their teams, and to relinquish a degree of control (especially if they’re in an oversight or gatekeeping role that’s outside a team’s own reporting hierarchy). But the longer we keep it, the longer we’ll be stuck in a non-agile past.

A huge amount of mental energy goes into ppl trying to justify/rationalize/inject waterfall thinking into Agile. Estimates, up-front architecture & other rigid plans, tactical roadmaps—all waterfall artifacts that hinder, not help. That energy would be better spent working.

— Allen Holub. https://linkedIn.com/in/allenholub (@allenholub) August 16, 2022

Interested in learning more? Unit 3 on Iteration of the Teaching Public Service in the Digital Age publicly-available syllabus is a great, in-depth read. This Beeck Center case study – Lessons from the Digital Transformation of the UK’s Universal Credit Programme – is also a fantastic summary of what doing this work well looks like.