Shipping

It is very, very difficult to “get things out the door” in government

One of the terms that comes up often in digital government work is “shipping”. In a word, it captures a lot of what it means to improve government IT, and why it’s difficult.

What does it mean?

When you think of shipping, you might think of Amazon delivering a package to your house. It’s not a bad comparison: there’s somewhere where the package came from (a factory, a wholesaler, an Amazon warehouse), there’s some steps involved in between (maybe a cargo ship and Canada Post), and there’s you – the person receiving the package at the end of the line. Something was shipped successfully when it made it from where it started (without getting lost or breaking!), to you, where you can benefit from it.

In the context of government work, the metaphor is basically: something has “shipped” when it has made it from inside government, to outside. If you can access or use a government thing, as an everyday member of the public, it’s shipped!

What’s the big deal with shipping?

There’s a reason that shipping is a catchphrase of digital government teams around the world. The bottom of the original 18F website said, “Always be shipping”. GDS’s unofficial motto is, “The Strategy is Delivery”. They have awesome posters with that written on it.

The reason these teams define themselves using shipping-related catchphrases is that shipping, in government, tends to be a rare and complicated thing.

In government environments, it’s very comfortable and very safe to write planning documents, strategies, IT requirements, and other internal reports. Making something that will reach the public – and getting all the way through a daunting process of approvals and reviews in order to do so – is much more difficult. Even for things that, from the very beginning, are meant for public consumption, it’s common for them to get derailed or stopped before they make it out the door.

Why is shipping so hard?

When things interact with the actual public, it’s easy for people in government environments to get nervous. Whether it’s an IT team putting together a new service, or a communications team writing a new blog post or publication, when a thing is heading towards the door it’s easy for an entire department’s “immune system” to react. Examples of this could be,

- A separate Quality Assurance (QA) review of a service, step by step

- Comprehensive project management documentation requirements

- Committee approvals (at several layers) to get permission to launch

- Privacy and security assessments, often undertaken by separate teams

- Communications plans that are scheduled separately from the thing itself

- A formal launch by a minister or other political representative

- Deployment of the thing onto production infrastructure, often done by a separate team or separate department

All of these steps tend to kick in as a thing gets close to being ready for the public – all intended to minimize risk and make sure that there isn’t any kind of negative reaction when the thing goes out the door.

The downside, though, is that – taken together – these steps make it difficult and time-consuming for a thing to make it out the door at all. Worse yet, it places a heavy burden on the original team, which has to navigate through all of these processes (sometimes several times over) to be successful. Meanwhile, the public service counterparts responsible for a given step might only be focused on or aware of their own process, and not how it contributes to a larger accumulation of complicated steps.

Imagine if, each time Amazon mailed you a package, it had to go to a review committee to decide if it could mail it or not. It probably wouldn’t ship packages nearly as often as it does today.

Why does it matter?

When things do finally make it out the door, after getting through the long and complicated gauntlet above, they’re often several years out of date. Or, they might not be user-friendly enough for the people that were supposed to benefit from them to use them.

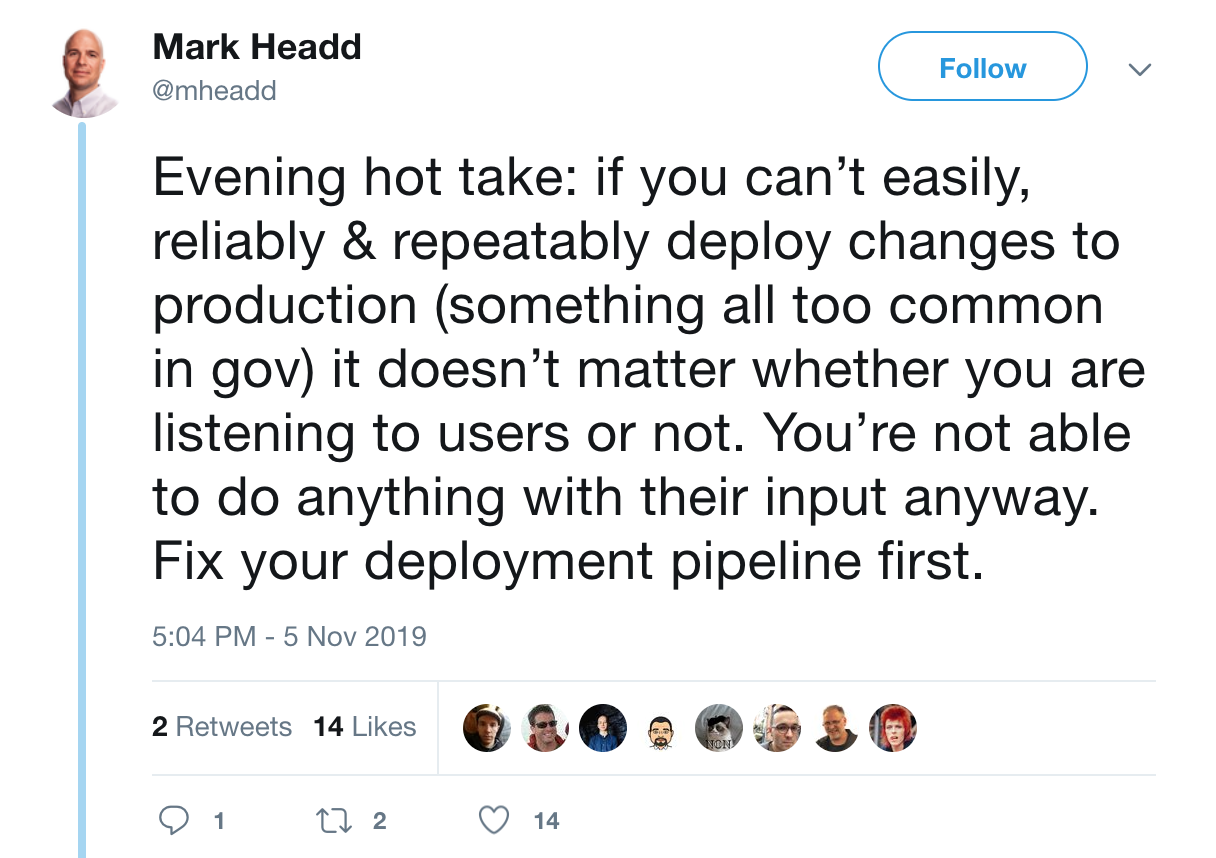

There’s a really important reason why digital service teams focus on shipping, and on shipping more effectively, more easily, and more frequently.

Getting something from inside to outside government means that you can start getting feedback from the people that are ultimately meant to benefit from what you created. Not just from internal stakeholders, not just from other public servants, and not just from hand-picked members of the public in an advisory or consultation group, valuable though these groups may be. From the actual public, which (for services and other products meant for the public) is the most authentic and effective source of feedback you can get.

A recent 18F blog post captures this really well. Rather than a product launch being the end of the journey, it’s actually just the beginning:

A product team learns. It learns about the needs of its users (through user research) and about the tech choices and tradeoffs involved in meeting those needs (through software engineering).

“Keeping it running” post-launch should not be the goal. Your software launch is an opportunity to start getting feedback from users and making improvements based on what you learn. In other words, it is a starting point.

How to make shipping easier?

Technology companies like Shopify ship changes to their live services hundreds of times a day without a dedicated QA division. They invest a lot of time and effort in tools that make shipping reliable and easy. That frequency is noticeably different from government IT groups, who typically publish updates a few times a year.

Getting there involves a lot of changes to how governments typically operate – both cultural changes and operational changes. Moving away from all the challenging steps above (or, for the ones that add value, figuring out how to do them more quickly and effectively) is difficult.

Here’s a few potential approaches that can help. Depending on what you work on (online services, communications products, policy documents) different ones might apply:

- Build QA directly into your development process, through things like linting, automated testing, and continuous integration

- Adopt agile software development techniques, and stop doing traditional project management documents

- Get executive support in advance to shield your team from various committee processes

- Seek delegated communications authority rather than going through a central comms division

- Use personal blogs and social media to talk about your work, while you wait for more formal communications channels to come online

- Reduce internal approval layers as much as you can

- Turn any unavoidable approval processes into templates that you can complete quickly

- Use cloud infrastructure that your team controls directly, to avoid having to wait for outside teams

- Publish your software as open source on GitHub so others can learn from it even if it hasn’t launched yet

- Write “infrastructure as code” to make system administration work as automated and consistent as possible

- Bake security and privacy best practices into your work from the start

If you’re curious what this looks like for IT infrastructure, Pete Hodgson’s “Hello, production” post is a great place to start.

Try as many of these as you can; any step that helps get things you work on “out the door” is a step in the right direction. It takes time to get to the level where you’re shipping, as the metaphor goes, hundreds of packages a day. But you can think of the small steps like, getting an envelope into someone’s mailbox. It might not make you a shipping mogul, but it’ll probably still make their day.