Worth reading: Government from home & A Shared Future of Work

Public service departments’ “return to office” plans have been a hot topic over the past few weeks. After more than two years where a large proportion of the federal public service switched to working from home, departments are planning to require that staff come back into the office at least a certain number of days per week.

Meanwhile: COVID-19 is still happening.

The reaction to messages and town halls from public service leaders as these plans have been announced hasn’t been pretty. Amidst all of this, Michael Karlin and Steph Percival wrote a couple of pieces over the past week – Government from home and A Shared Future of Work – that capture the present moment incredibly well. Everyone in the federal public service should read them both.

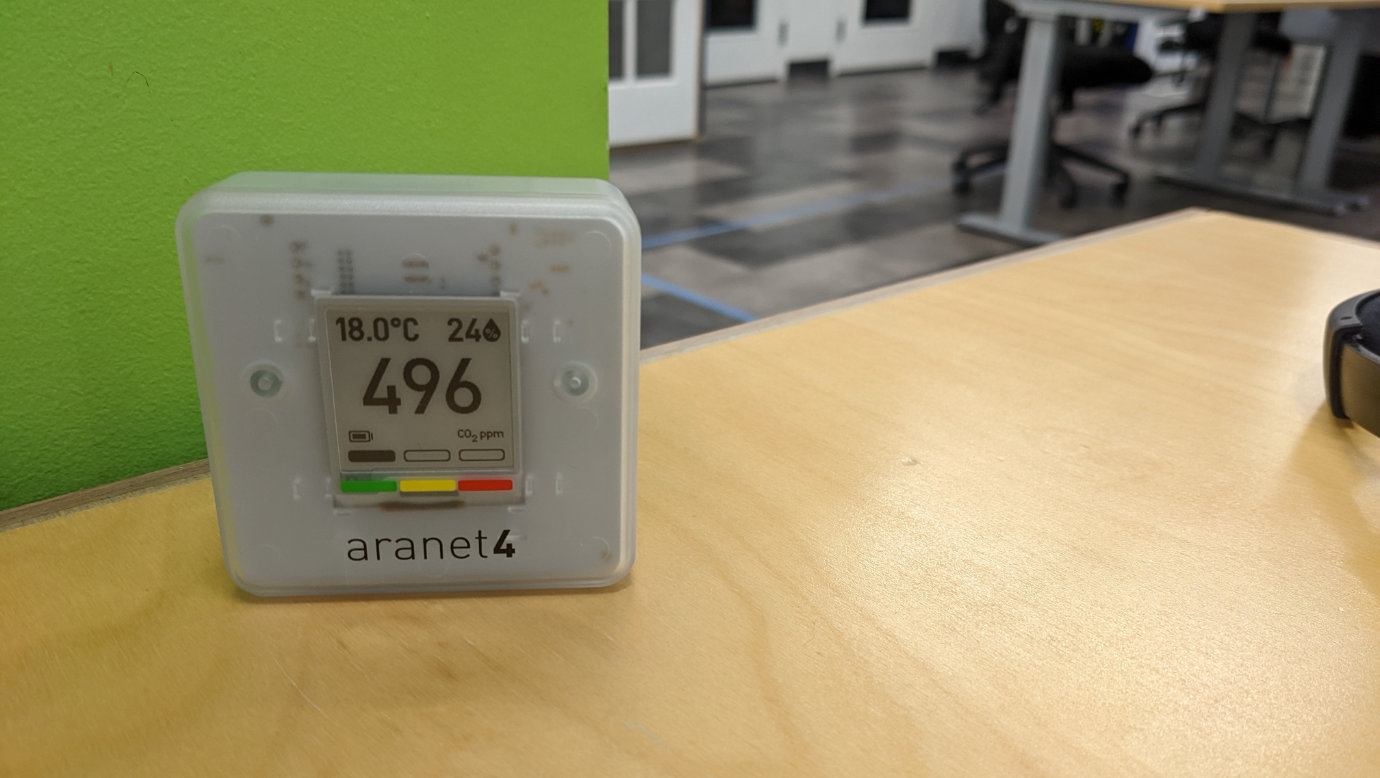

In addition to the steps that government departments should take to make returning to offices safer – open data on exposures, CO2 meters on building floors and ventilation improvements, mandatory mask mandates, and changes to sick leave and additional sick days – Michael points out that a return to office along pre-2020 lines has implications for national security and government continuity that thus far haven’t been part of the conversation:

Looking beyond the individual worker lens, there are very real national security and continuity of government concerns to have teams brought together in a single, indoor physical space for mandatory “anchor” days. BA.5 being incredibly infectious, it can introduce the possibility that entire teams become infected, leading to a situation where work of that team simply stops or people are pressured to work through their illness. Public servants are incredibly dedicated and already I’ve seen several in different departments work through COVID infections or significant Long COVID symptoms at home. This unwavering dedication can make their symptoms last longer.

Moving beyond the pandemic — or at least this one (looking at you, monkeypox) — we have to think about climate change and infrastructure. 2022 has been a particularly wild weather year worldwide. It is highly probable that continued climate change will bring increased changes of extreme weather events that will test our infrastructure. Just look at the May 2022 Ottawa derecho that caused the most damage to our electric transmission infrastructure in history.

This means that even if there is a return to offices, teams should not return together to the same office. Ideally there is some degree of dispersion, and even more ideally this dispersion is beyond the same city. The strategy should be to minimize the threat surface to any given function of state. Therefore if there is a bad outbreak on a floor of an office it may only affect a small amount of capacity from several teams than a large amount of capacity from one.

There are a lot of benefits to working from home: reduced greenhouse gas and climate change impacts (from less commuting), more flexibility for parents and caregivers when they need it, a reduction in workplace harassment and discrimination, a more adaptable working environment for people with disabilities, and a public service that more broadly represents the geographic and cultural diversity of Canada.

Remote work is an accessibility issue. It can significantly reduce barriers to work for people with disabilities. The false narrative that working remotely, especially from home, is not "real work" or "lazy" is extremely ableist.

— Ahmed Ali (@DrAhmednurAli) July 21, 2022

If you think collaboration is best done in-person you might: be an extrovert, be neurotypical, be white, not have a disability, have not yet had a good digital collab experience.

— Rachel Muston (@rachelmuston) July 20, 2022

Even if none of these are sufficiently compelling arguments, then purely for the sake of business continuity departments and public service leaders should be thinking about a geographically-dispersed future workforce.

Workplaces where people thrive

Steph’s piece looks at the bigger picture of how workplace decisions are made, how they are implemented and communicated to staff, and what it means to have workplaces where people thrive:

The design challenge posed by modernizing how and where we work isn’t simple. The fact is there are people who thrive working from home, people who thrive working in a traditional office setting, and people who thrive from having the fluidity to move between the two with ease.

When it comes to building flexible workplaces, there’s an entire spectrum of work that needs to be considered, from location-specific roles that allow for little flexibility (think on-site service delivery, for example) to roles that can be effectively completed from home 100% of the time, and everything in between. Most organizations have roles that fall into every category on this spectrum, so even within a single department or agency, creating one standard to rule them seems insensible.

Yet it seems that many organizations are taking the approach of setting a 2-day in-office standard, even – bafflingly – for people who don’t work in the same city as the rest of their team, for the purposes of experimentation.

Given how the return to offices has been framed as an experiment, Steph looks at how experiments should be structured – as a process for systematic and transparent learning – and at ethics considerations when conducting experiments that involve people. Her reflections on what a better future could look like are absolutely spot-on.

Power dynamics and “hybrid” work

Conversations about the return to office and hybrid work have been confusing (to employees and executives alike) since the word “hybrid” tends to be so nebulously defined. Generally it tends to mean, “some mix of in-the-office and at-home work”, particularly in contrast to either fully remote or fully in-the-office approaches, as Steph describes above.

The challenge is that there is a large and fundamental difference between “a mix, but according to the instructions and schedule of the employer” and “a mix, but at the employee’s discretion”. The “what” might look identical in both cases (e.g. employees coming into the office some but not all of the time) – hence the confusion – but the power dynamics in both situations are near-opposites.

Being able to choose if and when to come into the office lets employees make choices that reflect their best working styles and their level of comfort or concern about COVID-19, and to adjust these individually as the pandemic continues to evolve. Progressive organizations will keep that level of employee choice when the pandemic ends, I’d expect, to improve employee happiness, productivity, and retention.

Knock-on effects

Decisions like these don’t happen in a vacuum. In the case of return-to-office plans, I can only guess that one of the upstream factors is public and political dissatisfaction with the quality of government service delivery over the past few months. Kathryn May’s newsletter offers a good summary of this.

In the face of widespread public dissatisfaction with overwhelmed passport processing, slow airport security and customs lines, and other disappointing points of interaction with the federal government, the idea that public servants are uniquely able to work from home adds another layer of resentment. Public perception that government workers are coddled or lazy has political consequences, especially when it is (even if inaccurately) seen as a root cause for poor-quality service delivery to citizens.

Essentially: a premature and unsafe return to office is the belated political cost (to working-level and executive public servants alike) of decades of under-investment in public-facing service delivery.

Avoiding this, of course, would have meant investing in significant improvements to public-facing services years ago – alongside changes to public service culture and organizational processes needed to make those improvements feasible. As the saying goes, the second-best time to make these changes happen is right now.

A loss of confidence…

The downstream effect of current return-to-office plans is also worth thinking about. The most immediately-visible result is a loss of confidence (on the part of working-level public servants) in public service leadership. Town halls and messaging has been perceived as out-of-touch and elitist. Underlying rationales and evidence (if any) behind decisions and timelines haven’t been shared. As other commentators have said – the concern isn’t just that leadership decision-making on return-to-office plans is out of touch; it’s that leadership decision-making in general is.

(As a caveat: my perspectives on this at the moment are all second-hand. Departments aren’t homogenous entities, and from what I’ve heard some public service leaders have shared the pressures they’re under with a lot of candour and openness. If that’s you, you’re awesome. Keep on rocking.)

For leaders across government, a pressing question is how to repair a sudden and significant loss of trust in the decisions that they’re making, on the part of their staff. I don’t know what that looks like (and I am, very gratefully, not a manager or executive) but I think a first step would be to admit that mistakes were made here, and to postpone or change at least some parts of return-to-office plans. And to thank working-level public servants for sharing their concerns and feedback! The public service has a very strong hierarchy, which could make it tempting for leaders to ignore these reactions and double-down on current plans; I think that would be an error. Daniel Blouin’s thread on how managers can protect their employees from poor-quality decisions made further up the hierarchy is also an important reminder.

…and a loss of good people

The longer-term downstream effect is, of course, the loss of talented and capable public servants to other employers (either to other levels of government, non-profits, or the private sector). It’s already incredibly difficult for the government to hire people in specialized technical fields (like data science and software development); forcing a return-to-office and relocation to the National Capital Region will definitely make this problem worse.

In the case of at-scale changes that have negative effects on employees (like hiring or salary freezes, workforce reductions, or, in this case, returning to physical offices during an airborne pandemic), there’s also a filtering mechanism that takes place. In the public service, despite an array of performance measurement activities (like annual PMAs), it can be hard to effectively differentiate high-performing and under-performing employees. High-performing employees (fast workers, creative thinkers, institutional memories and foundations of their teams, etc.) often don’t have the time or patience for individual performance-reporting activities, while under-performing employees can become adept over time at gaming these systems to appear more productive. The rates at which public sector organizations fire people is also vastly lower than in the private sector.

In that context, the best measure of high-performing versus under-performing employees is that high-performing employees can get jobs elsewhere, and will, when the working environment they’re in, in the public service, gets worse. Under-performing employees will stick around, and the overall capacity of the public service will get worse on average as a result. Learning that a team-wide, department-wide, or government-wide change in working environment has led to a great employee’s departure is a really unfortunate time to discover that.

Poor feedback loops between employees and senior public service leaders is a chronic problem. Given the hierarchy and power dynamics of the public service, this can only change from the top down.

For perspectives on what a safer vision for adapting to COVID-19 would look like, Dr. Lisa Iannattone’s Twitter feed and Alanna Shaikh’s newsletter are both great resources.